YOU NEED EYES TO SEE THE SMALL THINGS

Veronica Pinheiro

21 August 2025

Children cry. And, through the salty drops, they communicate and express their physical and emotional needs. It is a way of releasing tension and saying, “something is bothering me”. If crying is communication, it always says something. Think of the discomfort of being left in the care of strangers without your consent for hours, five days a week. Children are starting to attend formal educational environments earlier and earlier. We call the process of introducing a child to school or nursery the ‘adaptation period.’ In short, it is a time for parents and children to adapt to new relationships and routines.

About children who stop crying more quickly, they say: ‘That child is adapted’.

Today, I question how much silencing is involved in such adaptation. An adapted child is different from a sheltered child. When well-being is not part of institutional motivations, all you need to know is whether a person ( child or adult) is adapted to the established dynamic; because being adapted is different from being happy. Humans need to give purpose to their practices and, by doing so, they adapt other humans while they are still children.

For two years now, we have known Kayque. From time to time, he goes back to crying at school. Sometimes he cries a lot. Whenever we talk about his crying at school, he replies: "You know I can't stay for too long. I get irritated. I cry." We have learned, through Kayque's crying, to insist on communicating what bothers us. He needs to adapt to a structure that does not adapt to him.

After the last day of crying and talking, we went to the opening of the Nature Readings laboratory.

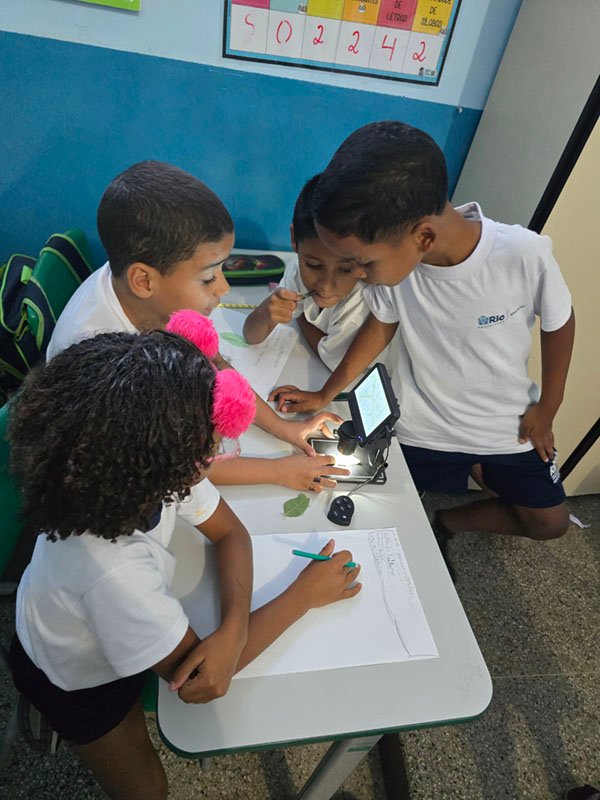

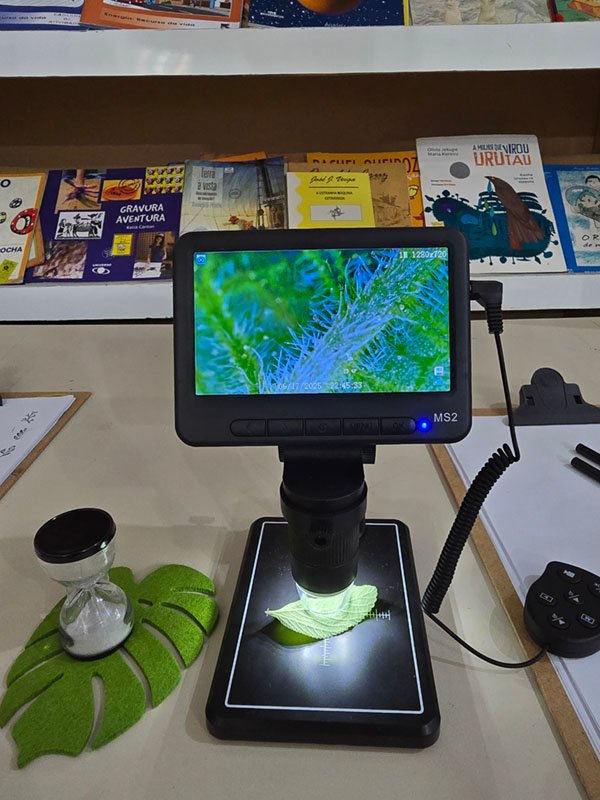

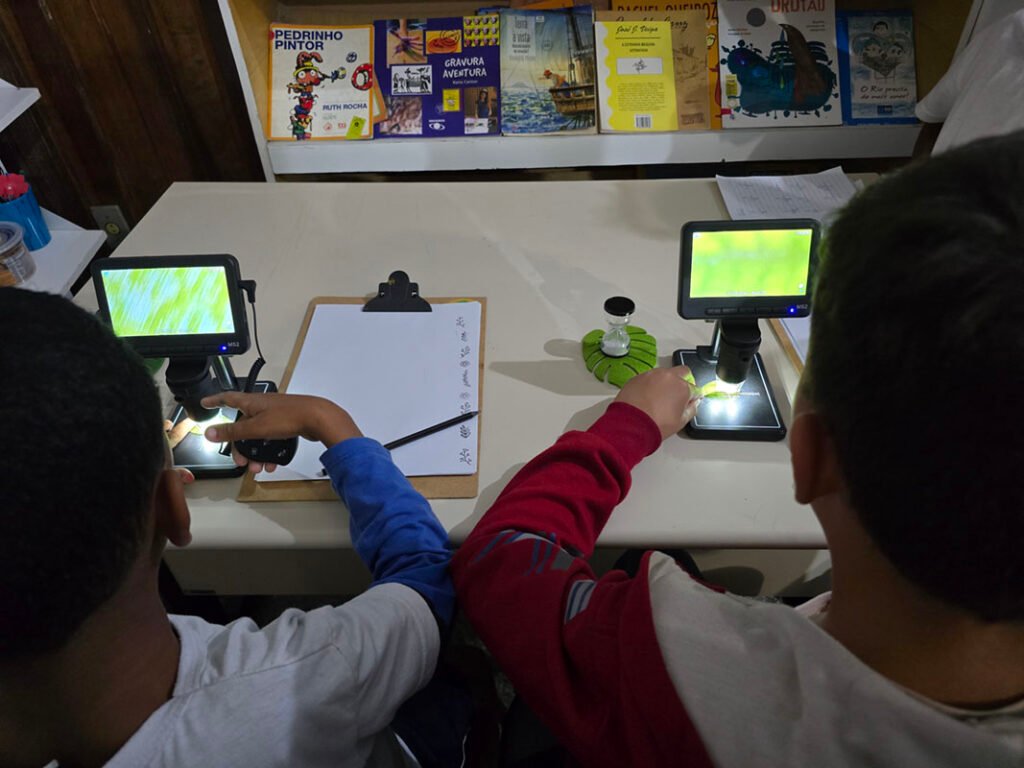

The Ways of Knowing Group is setting up a laboratory with microscopes to read plant leaves at Escragnolle school. A space dedicated to observation and reading, where, in our own way, we learn to understand what the plants in the school garden are telling us. Kayque's class had the task of observing the lemon balm that perfumes the school entrance. First, they touched the plant, caressing its contours and textures; then they smelled the leaves, flowers, and branches. Next, they drew what they saw. Kayque, due to motor issues, chose not to draw, but he joined in the activities. The students researched and talked about plants that heal while they waited, with some anxiety, for the moment to observe them under the microscope.

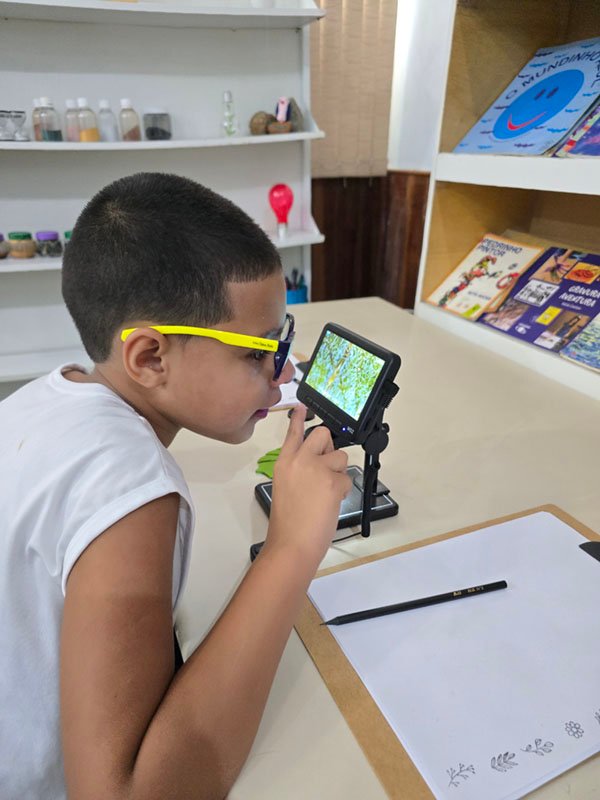

When we announced that we could see very, very small things under microscopes, Kayque started crying again. He communicated again. He is learning to put words and meaning to what he feels. This time, he seemed sad and said, "I can't run or do a lot of things. Now I won't be able to see who lives on the plant either. I won't be able to look through the “telescope”.‘ And he concluded: ’I wear glasses, not everyone has eyes to see the small things."

He was crying because he didn't want to be left out of an experience he had once seen on television. He also wanted to see who lived in the plant, like the other children in his class. The boy calmed down when he learned that the school microscope was different from the one in the book and the film; instead of eyepieces, our microscope has a screen.

With the devices turned on, we let curiosity guide the children's research. The fun of discovery made studying more beautiful. At that moment, Kayque and his friends saw what made the lemon balm leaf so soft: ‘This leaf has little hairs.’

‘The leaf is not entirely green as our eyes see it. There's yellow and white too.’

‘The greener leaf is softer, with more white droplets.’

For each small thing they identified, the nouns were carefully described with adjectives by the little researchers.

‘Miss V. said there are creatures living in these leaves. We have to find out who they are!’

The usual leaf, the same lemon balm leaf so familiar to children, was seen for the first time through a magnifying glass. And, as Kayque aptly summarised, the lens served to reveal the small things that the eye cannot see. Milena was the first to notice the creatures on the leaves. She, who usually shows impatience towards proposals, was silent, trying to see with her eyes, ears and nostrils. Words only found their way out of the girl's mouth when she identified identical dots that looked like worms. ‘I need to enlarge the image! Tell the leaf not to move. Silence. I saw it! It's pale yellow, it moves like a snake. There are lots of them here. We are not alone!’

Once the creatures living in the lemon balm leaves had been found, the research continued in search of the ‘right name to call the pale yellow worms’. Germs, bugs, bacteria, worms, micro-organisms. The experience became more and more beautiful as time went by. Narratives, stories of how those creatures got there, hypotheses and fabulations created sensitive records among the children. The plant's leaf was a dense book to be read without rush, as learning involves a complex system of interactions. By studying the leaf with curiosity and interest, children can develop essential cognitive, emotional, and social skills. Discoveries, even the simplest ones, stimulate critical thinking, language, motor coordination, and problem-solving skills.

Kayque's crying gave way to questions. And the research that began became a challenge. Having the eyes to see the small things was not enough for the boy. The act of seeing did not end there. Seeing small things was not the end, but the beginning of an active and inventive journey. Now that we had seen, we wanted to know more about the tiny creatures we had observed. Children teach us that once we have seen a being, we cannot ignore their existence. And since we do not walk alone, the images taken by the children were sent to a biologist with a PhD in earthworms. To the children's surprise, the creatures were not earthworms but springtails, small arthropods that are important for maintaining ecosystems.

From then on, the research became routine, and seeing the small things has become a daily exercise. We haven't seen Kayque cry in over a month. We hope he is feeling sheltered.

Photos: Veronica Pinheiro

Springtail Video Colêmbolos